By Kim Poirier

~The view from Bassae.

Built atop a remote mountain in the Arcadian countryside, the Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassae is an architectural marvel. Maybe. Probably. Allegedly. Look — this isn’t actually a post about the temple.

This is a post about tripping over your own traitorous feet in the middle of the Greek countryside.

How did you fall, Kim? That’s a great question. You see, the trouble with accidents is that they tend to happen in moments of inattention — which makes isolating the precise moment of error particularly difficult. Maybe I chose my footing poorly. Maybe my ankle gave out. Maybe the fault lies with the stones themselves. Or maybe Apollo Epikourios himself saw fit to humble me. Perhaps I offended his divine stature by committing a grave act of sacrilege — namely, drinking a crisp, cold Peach Fanta while touring the perimeter of his temple. Who can say? It’s all very ambiguous.

Here’s what I do know: I was heading down a rough-hewn stone staircase leading from the archaeological site’s bathroom when I felt the very unexpected — but not unfamiliar — sensation of the air opening up below me. Arms pinwheeling, I fell forwards and plummeted down the rocky slope.

Speaking objectively, it probably only took half a second for my body to go from bipedal to sprawled across the stones. But, as the terminally clumsy know well, something exceptionally strange happens to your perception of time in the moment where you first lose your footing. Everything seems to slow down, to elongate. Each millisecond passes with the weight of a full minute.

As I hurtled towards the earth, doomed by the predictable operations of gravity, I contemplated the possible consequences of my forthcoming impact. How far was I from the others? Would anyone be around to see it? If so, would they gasp in alarm? Would they rush to my side? Would they guffaw nervously? Would my falling be pathetic, I wondered, or funny? Would falling on my face outside the Temple of Apollo Epikourios somehow make me more interesting, or perhaps endearingly clownish? If I broke something — a tibia, maybe — how would the next hour proceed? How would the next two weeks proceed? How badly would I inconvenience my professors? I even had time to be reminded, however briefly, of a passage from a much-beloved Emily Dickinson poem,

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down –

And hit a World, at every plunge

I hit the limestone like a trashbag hits the curb: gracelessly, unbeautifully, and without comedy. Bewildered, I braced myself on all fours, palms stinging where they’d skidded against warm, porous rock. Two seconds of blinkered self-assessment. Three at most. Once I was assured that nothing truly dire had occured — bruises, nothing more — I clambered to my feet. I was sore, chastened. But I was fine.

Upright once again, I threw a glance over my shoulder. I was anxious, at first, that I had humiliated myself, that someone from our study group had watched me launch myself down a rocky ledge. As it turned out, I needn’t have worried. All around me, there were trees and stones and silence. I was alone.

My relief came twinned with a paradoxical stab of disappointment. Such is the beauty and the mystery of falling on your face in the remotest Arcadian mountains; it sucks if you’re witnessed, but if there were no witnesses at all, then what was it all for?

Look. Travel can be sexy, glamorous, luxurious. It can be crystalline waters and panoramic views and gorgeous museums full of Attic grave stelae. It can be picturesque, envy-inducing, ego-fellating.

But not always. Sometimes, it’s breaking a wine glass at a tasting in Nemea. Sometimes, it’s scrubbing your underwear in a hotel sink. Sometimes, it’s sitting hunched up in your room and carefully draining the fluid out of your blisters. And sometimes, it’s eating shit on a small, rocky slope outside the Temple of Apollo Epikourios.

You take the good with the bad — the moments of erudition with the moments of humiliation, the moments of pain with the moments of comfort, the splendour of a remarkably preserved bronze statue with the monotony of a long line to use a public toilet. You do all this, knowing that it’s worth it — worth it for that one, perfect moment where you can feel the past reaching a hand out to touch you.

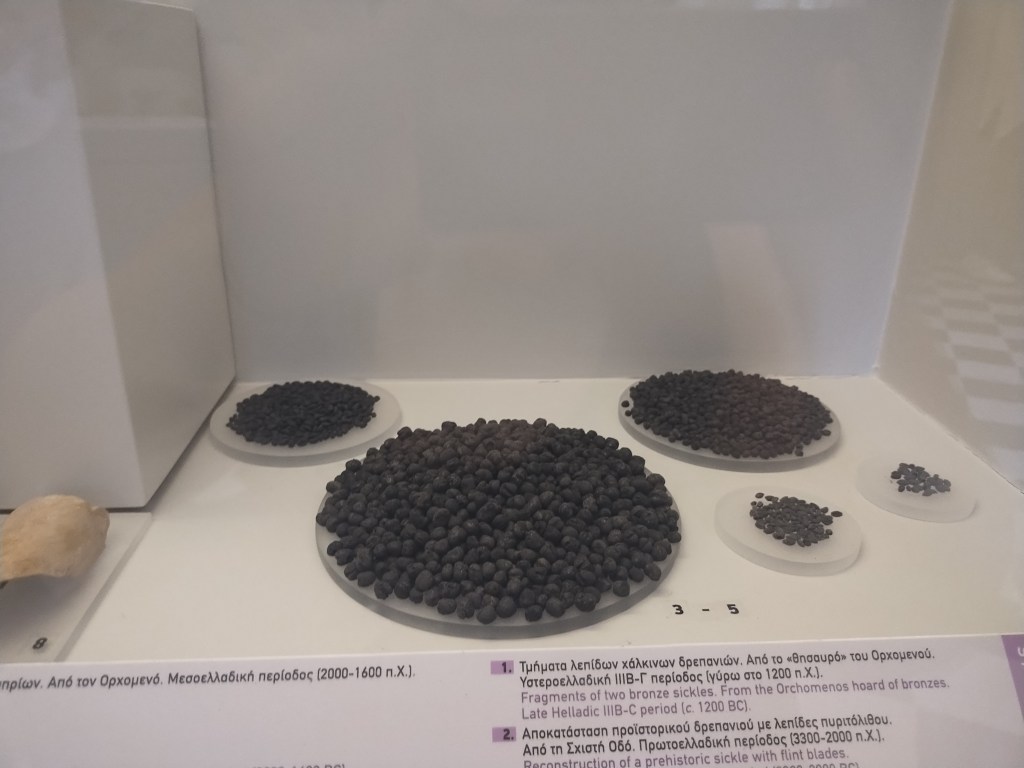

That moment comes at different times for different people. For me, personally, it came to me today when I stared down at a small handful of carbonized broad beans and emmer wheat. Don’t ask me to explain myself; I couldn’t if I tried.

~Carbonized seeds dated to the Bronze Age, indicative of the Ancient Greek diet, Chaeronea Museum.

Leave a comment